Fig. 1

Robert Peake (1551 – 1619)

Fig. 1

Robert Peake (1551 – 1619)Called Arbella Stuart (1575 – 1615)

Oil on panel: 61 x 37 in. (154.9 x 93.1 cm.)

The Duke of Bedford.

Fig. 2

Robert Peake (1551 – 1619)

Fig. 2

Robert Peake (1551 – 1619)Francis Russell, 4th Earl of Bedford

Oil on panel: 50 x 30 ½ in. (127 x 77.5 cm.)

The Duke of Bedford.

Fig. 3

Robert Peake (1551 – 1619)

Fig. 3

Robert Peake (1551 – 1619)Henry, Frederick, Prince of Wales (1594 – 1612)

Oil on canvas: 172.7 x 113.7 cm.

Painted circa 1610

© National Portrait Gallery, London.

Fig. 4

Robert Peake (1551 - 1619)

Fig. 4

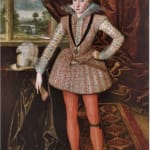

Robert Peake (1551 - 1619)Charles I (1600 - 1649)

Oil on canvas: 158.8 x 87.6 cm.

Painted 1613

© The Old Schools, University of Cambridge.

Robert Peake (c.1551 – 1619)

Further images

Provenance

(Possibly) Anne Gilchrist (1828 - 1885), née Burrows; to her son

Herbert Harlakenden Gilchrist (1857 – 1914), Hampstead, by 1907;

Arthur Thomas Filmer Wilson-Filmer (1895 – 1968); his sale

Christie's, London, 27 June 1945, lot 712 (as by Isaac Oliver);

David L. Style (1913 - 2004), Wateringbury Place, Maidstone, Kent; his sale

Christie's, London, 1 June 1978, lot 346 (as by Robert Peake the Elder);

Christie’s, London, 19 November 1982, lot 74 (£8640); where presumably acquired by the previous owner.

Literature

R. Strong, The English Icon, London and New York 1969, p. 244, no. 219 reproduced (as Robert Peak the Elder);R. Strong, The Tudor and Stuart Monarchy, vol. II, Woodbridge 1995, p. 261, no. 219 (as Robert Peak the Elder).

Such was the artist’s standing, the patron of the present work, almost certainly the boy’s father, must have held a significant position within the court. Indeed, for much of the last century, the sitter was thought to have been Henry Frederick Stuart (1594 – 1612), the Prince of Wales. Whilst there are several factors that make this a plausible theory, such as the distinctive ostrich feathers that decorate the felted wool hat - this decorative plumage being similar to the heraldic motif for the Prince of Wales - and Peake having been first appointed the picture maker to Prince Henry in 1604, the unbreeched boy is demonstrably too young to be the prince.[1]

The abundant plumage within the boy’s brimmed hat is punctuated by an ‘aigrette’ (a hat jewel), which were commonly used to adorn hats within the Jacobean court. Many of these can be linked and attributed to the Dutch goldsmith Arnold Lulls (fl. 1580 – 1625) as an album of over forty of his designs survives in the Victoria & Albert Museum in London. The jewel shown here appears to be a pendant consisting of table-cut diamonds set within a linked gold-enamel setting, from which hangs a large drop-pearl.[2] Similarly elaborate hats are also shown in portraits of Prince Henry and his younger brother, the Duke of York (later Charles I), by Robert Peake (Figs. 3 & 4).

Whilst the composition is straightforward, and the overall imagery is dominated by the contrast between the sitter’s soft white costume against the textured fabric and wooden surfaces, the portrait contains two particularly curious symbolic elements: the little boy holds in each hand - rather awkwardly - a ruddock (i.e. a robin redbreast) and a stem of cherries. Both motifs have been purposely included to symbolically allude to various morals, which would have been pertinent to the subject and their family. The colour of the redbreast naturally instils a feeling of warmth, though it can also signal a warning; according to various Christian texts, the robin used to be brown, but ‘earned’ its redbreast whilst it was fanning a fire to keep the Christ Child warm in his manger. The same can be said of the lusciousness of cherry red: whilst on the one hand it whets the appetite of their possessor, who knows of the fruit’s delicious sweetness, it is also warns one of its seasonal nature and delicacy, which is akin to the fragility of life.

Children were immensely vulnerable in the early modern age - the majority never reaching adulthood - so there is no coincidence that the morals implied here by the robin redbreast and the stem of cherries relate to the preciousness of life. However, without knowing the direct intentions of the artist and his patron, their meaning today is somewhat ambiguous. It seems most likely that the sweet, seeded fruit may indicate hope for the child’s future, as in Christian iconography cherries represent the sweetness of Paradise (i.e. a good, healthy life), with the robin protecting the child’s susceptibility to life’s dangers. It is also tempting to speculate whether the robin redbreast was added after the portrait was finished to represent a loss sustained by the family within the child’s lifetime; historically the bird has been recognised as an aide-mémoire for lost family members, appearing in the absence of those departed. With this in mind, it reiterates the undeniable presence, and historical value, that a portrait painting can convey as an object, as they can cleverly immortalise its subject.

A more literal interpretation of the bird included within this portrait could aid one in identifying its sitter: whilst they were more commonly known as ‘ruddocks’ in the early modern age, it is possible that the robin redbreast bird was purposefully chosen here to signify the subject’s name as being Robin. Whilst it was not a common name, Robin is also nickname for Robert; ‘-in’ being a diminutive suffix, indicating that ‘Rob’ is short for the non-suffixed word – here being ‘Robert’.

Unfortunately, it has not yet been possible to positively identify the sitter on the basis of the painting’s historic provenance, but it is possible to rule out the sitter being an ancestor of the earliest known owner of the painting, Herbert Harlakenden Gilchrist (1857 – 1914), as he was descended from the Harlakenden-Carwardine family of Earls Colne in Essex, who were landed gentry, but never members of the nobility. As Peake was a ‘Serjeant Painter’ to the court when this portrait was commissioned, his clientele would have been exclusively members of the inner court or nobility. The son of Alexander (1828 – 1861) and Anne Gilchrist (1828 - 1885), Herbert Harlakenden was a respectable artist, who exhibited at the Royal Academy in London and the Philadelphia Academy of Fine Arts. His father was a noted art critic and historian, who penned the biographies of the artists William Etty and William Blake, and his mother was a respected author and long-time correspondent of the American poet Walt Whitman. It is more than plausible that the present portrait was acquired by the Gilchrists in the late nineteenth century, due to Alexander’s interests and active participation within the London art world.

Robert Peake is today one of the best known of the artists working in England during the reigns of Elizabeth I and James I. He had a relatively long and successful career as a portraitist; first to the minor nobility and landed gentry of late Elizabethan England before becoming, after the accession of James I in 1603, a member of the Royal Household as principal ‘Picturemaker’ to the young heir to the throne, Henry Frederick, Prince of Wales. In 1607 he was appointed ‘Serjeant-Painter’ to James I, a position he held jointly with John de Critz (1551/52 – 1642). Peake was born into a Lincolnshire family in around 1551 and first worked as an apprentice to a goldsmith in London’s Cheapside district. In 1576, after becoming a Freeman of the Goldsmith's Company, he went on to work for the Office of the Revels, where he was one of the six ‘Paynters and others’ responsible for the preparations for the Court festivities at Christmas, New Year, Twelfth-night and Candlemas in the winter of that year. Peake continued doing decorative work for the court for several years until he was well enough established to start his own studio. By 1598, when he was recorded in Francis Mere's Palladis Tamia, he was regarded as one of the most important painters then practicing in England.[3]

Upon the accession of James I in 1603, Peake was commissioned to paint portraits of the two elder Royal children: the resulting paintings, Henry, Prince of Wales and his friend Sir John Harington of Exton after the hunt’ (Metropolitan Museum, New York), and its companion, that of Princess Elizabeth, later Queen of Bohemia, (previously with The Weiss Gallery, now The Queen’s House, Greenwich) were, with their inter-related landscape settings, two of the most ambitious and original images yet seen in British royal portraiture.[4]

Peake's oeuvre was long obscured mainly due to there only being one surviving signed work, a portrait of an Unknown Military Commander, which is now in the collection of the Yale Center for British Art, and one documented painting. 4 The latter is another portrait of Charles I, as Duke of York, which Peake painted a year or so after ours, in 1613, a commission for the University of Cambridge and for which the receipt for £13 6s 8d still survives.[5] On the basis of the Yale portrait, which is inscribed with the artist’s name on the reverse of the panel, a substantial corpus has now been identified using the idiosyncratic and particular manner with which Peake inscribed the date and the age of his sitters. The earliest portraits to be identified in such a manner are dated 1587.[6]

The present portrait was first identified as a work by Robert Peake by Sir Roy Strong in his seminal book on early English portrait paintings, The English Icon, which was published in 1969 (no. 219). Amongst other stylistic indicators of its authorship, our sitter has a typically Peake-like elongated face and modelled mouth and eyelids. There are several particularly comparable works by the artist, painted between 1603 and 1610, which also show noble children accompanied by animals in full-length format (Figs. 1 & 2).

[1] In the seventeenth century, when a boy reached the age of six, it was usual for him to be ‘breeched’, i.e. he graduated from wearing skirts to breeches (trousers), an event which was a proud and celebrated family occasion.’

[2] For a comparable jewel, see: https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O915604/designs-for-jewellery-by-arnold-album-lulls/

[3] M. Edmond, “New Light on Jacobean Painters” from The Burlington Magazine, vol. 118, 1976, p. 78.

[4] These two works were likely painted for the Haringtons of Exton, and they subsequently descended within the Lords North at Wroxton Abbey. See: M. Weiss, “Elizabeth of Bohemia by Robert Peake: the problem of identification solved” from Apollo, vol. 132, 1990, pp. 407 - 410.

[5] Payment was made on 10th July 1613 ‘in full satisfaction for Prince Charles his picture’. See: A. J. Finberg, “An Authentic Portrait by Robert Peake” from The Walpole Society, vol. 9, 1920-21, pp. 89 - 95.

[6] Arthur, Lord Grey de Wilton and Humphrey Wingfield. Reproduced in Strong, ibid, p. 229, as nos. 190 & 191 respectively.