Pierre Delorme (c.1716 – 1776), after Louis Tocqué (1696 – 1772)

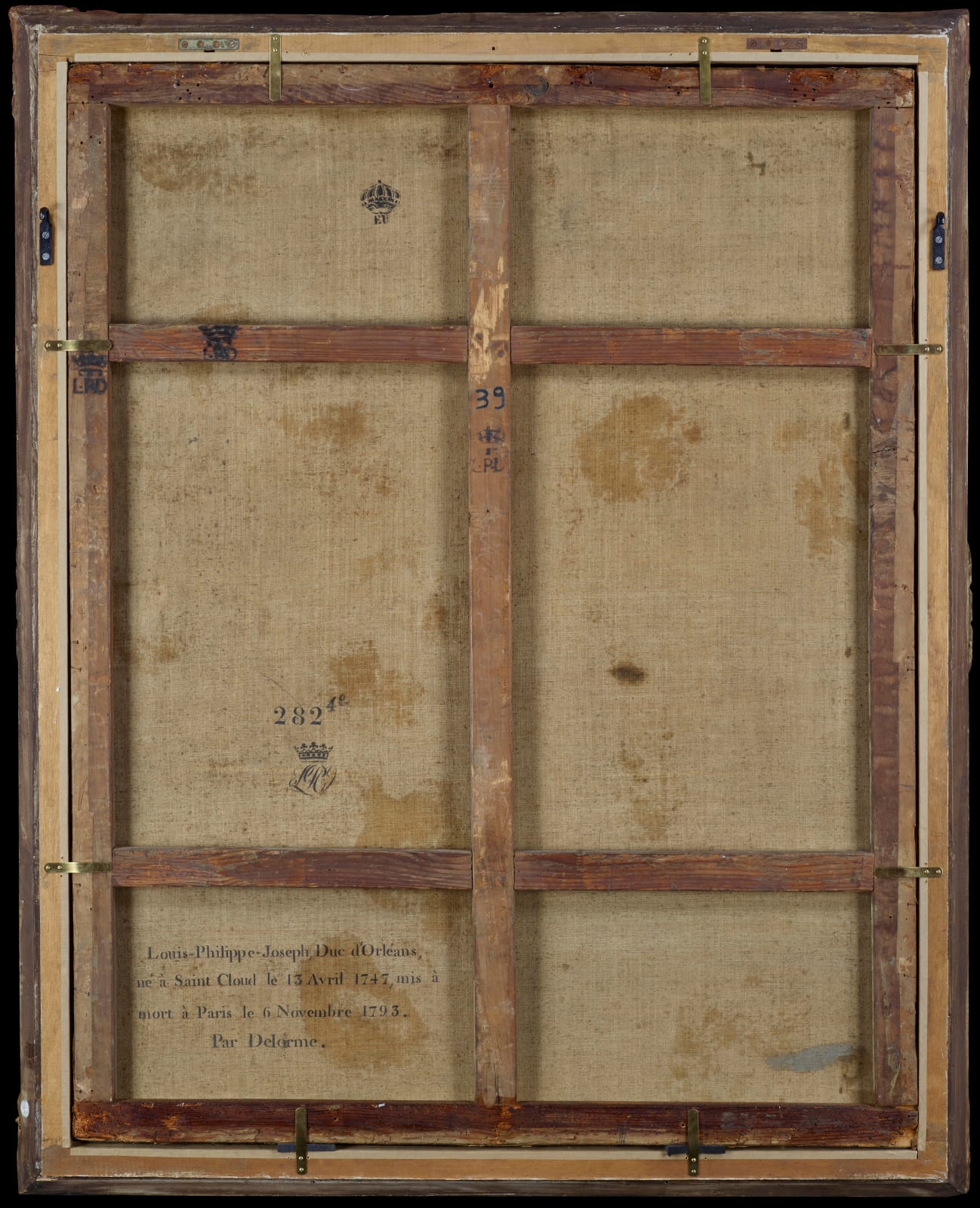

Stamped verso with the French royal cipher and inscribed: ‘2824 / Louis-Philippe-Joseph Duc d’Orléans, / né à Saint Cloud le 13 Avril 1747, mis / mort à Paris le 6 Novembre 1793. / Par Delorme.’

Provenance

Likely commissioned by the sitter’s father

Louis Philippe I (1725 - 1785), duke of Orléans, château of Saint-Cloud; until circa 1780 when likely gifted to the sitter

Louis-Philippe-Joseph II (1747 - 1793), duke of Chartres, upon his taking possession of the Palais-Royal, Paris; following his execution, by guillotine, on 6th November 1793, the legal claim to his estates passed to his widow

Louise Marie Adélaïde de Bourbon (1753 – 1821), duchess of Orléans, château of Eu; to her son

Louis-Philippe, duke of Orléans (1773 – 1850), ‘King of the French’, château of Eu; to his second son

Prince Louis of Orléans (1814 - 1896), duke of Nemours; to his son

Prince Ferdinand Philippe of Orléans (1844 – 1910), duke of Alençon; to his second son

Prince Emmanuel, duke of Vendôme (1872 - 1931), Neuilly-sur-Seine; his sale

Galerie Georges Petit, Paris, 4 December 1931, lot 62 (15,000 francs); bt. by

Léon Cotnareanu (1891 - 1970), Paris; by whom likely sold at

Palais Galliera, Paris, 14 December 1960, lot 4; (possibly) bt. by

Galerie Kugel, Paris;

Private collection, Italy.

Exhibitions

Related works

Louis Tocqué (1696 – 1772), Louis-Philippe-Joseph II, Duke of Chartres, exhibited at the Paris Salon in 1755, no. 48.

Literature

Gautier-Laguionie, Indicateur de la galerie des tableaux des S. A. S. Mgr Le Duc d'Orléans, au château d'Eu, Paris 1824, p. 39, no. 236 [as being in château of Eu].

J. Vatout, Notices Historiques sur Les Tableaux de la Galerie de L.A.R. Mgr. le Duc d'Orléans, Vol. 3, Paris 1826, p. 317, no. 236 [as being in château of Eu].

J. Vatout, Le Château d'Eu, notices historiques par M. J. Vatout, Premier Bibliothecaire du Roi, Vol. V, Paris 1836, p. 194, no. 363ter.

P. Dupont, Indicateur de la galerie des portraits, tableaux et bustes qui composent la collection du roi au château d'Eu, Paris 1836, p. 230, no. 363ter.

É. Deville, Index du "Mercure de France", 1672 - 1832: donnant l'indication, par ordre alphabétique, de toutes les notices, mentions, annonces, planches, etc., concernant les beaux-arts et l'archéologie, Paris 1910, p. 61. [this refers to an engraving by Pierre Adrien Le Beau (1744/1748 – c.1817) after Delorme].

A. Doria, Louis Tocqué, Paris 1921, p. 130, no. 255.

Rémi Cariel, Étrange visage: portraits et figures de la collection Magnin, Dijon 2012, p. 128.

The young duke of Chartres, as Louis Philippe was then known, is here presented in clothes consistent with the opulent style of Louis XV’s court: sporting a carefully powdered wig, he wears a blue velvet jacket with gold buttons over a gold and floral embroidered waist coat, whose cuffs extend and turn up over the arms of his jacket. Lace shirt cuffs reflecting the lace at his collar extend over his hands, one of which holds his tricorn hat. His blue velvet britches match the jacket, with white stockings ending in black shoes with gilt buckles and striking red heels. The duke is shown feeding the swans kept within the ornamental pond of his father’s residence, the château of Saint-Cloud, with elegant purpose.[1] A hound to his left snarls jealously towards the boy’s now empty hand, presumably perturbed that the hunks of bread were intended for the royal birds. Despite the sense of a potential fracas, the young boy smiles away from the scene, likely toward a rose garden, the ends of which creep into the composition from the left side.

There must have been every hope of a glorious career for the young Louis-Philippe, born at the great château of Saint-Cloud, whose splendid park dominated a hilltop overlooking the west of Paris. Endowed with considerable estates and the position of third in line of succession to the French throne - only challenged by what some authorities considered the superior claim of the king of Spain - he had every chance to make the most of his good fortune. The duke’s father, also Louis-Philippe, called “le Gros” (the fat), was the duke of Orléans, a First Prince of the Blood, making him second in line for the French throne should the first family perish. He married a distant cousin, the 17-year-old Louis-Henriette de Bourbon-Conti, daughter of a junior prince of the blood royal, whose grandmother was one of the illegitimate children of Louis XIV. There was a certain hesitation about an alliance that would bring the blood of the illegitimate line into the Orléans family, but it was assumed that the young woman’s strict upbringing in a convent would have imbued her with sound Christian virtues, while her birth was well-compensated by her dowry.

Latterly, the duke of Chartres’s own matchmaking was equally concerned with seeking a handsome dowry; with his father’s encouragement he first sought a marriage to Princess Cunigonde of Saxony, the younger sister of the dauphin, Princess Marie-Josèphe of Saxony, but the king thought this was too important a match and would only serve to encourage the evident ambitions of the young duke. Instead, in 1769 he married the 16-year-old Mlle de Penthièvre, Marie-Adelaide de Bourbon who, thanks to the premature death of her only brother, the prince of Lamballe, was the greatest heiress in France; any doubts concerning her descent from another of Louis XIV’s illegitimate children were smoothed over by her vast fortune.

Louis-Philippe had first bore the title of duke of Montpensier, a duchy that carried with it a considerable estate that had been inherited by his great-grandfather, the regent, from the “grande mademoiselle”, then one of the greatest heiresses in France. With the death in 1752 of his grandfather, the Montpensier title was substituted with that of Chartres and in his new position he was removed from the care of women - not least because of the estrangement between his parents - and given into the care of a tutor, Emmanuel, count of Pons-Saint Maurice (1712 – after 1771). The latter was assisted by a notable cleric, professor and academician, Étienne Lauréault de Foncemagne, a friend of Voltaire and the great historian of the Roman Empire, Edward Gibbon, and the artist and playwright, Louis Carrogis de Carmontelle, who gave the young prince a solid foundation, encouraging his liberal and ultimately anti-clerical beliefs that were furthered by his joining the freemasons.[2] Louis-Philippe was also among the very first to be inoculated against smallpox, his father having been influenced by the Swiss doctor and encyclopédiste, Theodore Tronchin, a friend of Voltaire, Rousseau, and Diderot. His mother died in 1759 and his father successfully later sought permission from the king to marry, in what was called a ‘secret’ marriage to his second wife, Charlotte-Jeanne Béraud de La Haye de Riou, widowed marquise de Montesson;[3] as she came from a minor noble family a public, official marriage was considered unsuitable for a prince of the blood.

With his father-in-law Louis Jean Marie de Bourbon, Duke of Penthièvre (1725 – 1793) enjoying the title of grand admiral of France, the duke decided to pursue a naval career, his birth assuring him high rank. This indeed proved to be the case with him joining the navy as a cadet, in 1772, and in just six years he was promoted to lieutenant-general of the navy in 1778. In the same year he was put in command of a squadron that engaged the British navy at the battle of Ouessant. While he proclaimed this a victory, his errors had led to the British ships escaping and when the news of what really happened became public knowledge, he was quietly removed from further command.

Orléans’s hostility to Louis XVI’s queen, Marie-Antoinette (1755 – 1793), forced him to live away from the royal court of Versailles. During the conflicts that arose between Louis XVI and the nobles over financial policies in 1787, Orléans was temporarily exiled to his estates for challenging the king’s authority before the Parlement of Paris, one of France’s highest courts of justice. He was quickly elected a representative for the nobles to the States General, which convened on 5th May 1789. Orléans supported the unprivileged ‘Third Estate’ (i.e., the bourgeoisie) against the two privileged orders, being the nobility and clergy. On 25th June he and a group of nobles joined the Third Estate, which had, only a week before, proclaimed itself as the National Assembly. His Paris residence, the Palais-Royal, became a centre of popular agitation, and he was viewed as a hero by the crowd that famously stormed the Bastille on 14th July.

On returning from a mission to England in July 1790, Orléans officially took a seat in the National Assembly. He was admitted to the politically radical Jacobin Club in 1791. After the fall of the monarchy in August 1792, he renounced his title of nobility and accepted the name ‘Philippe Égalité’ from the Paris Commune, one of the popular Revolutionary bodies. Elected to the National Convention - the third successive Revolutionary legislature - which convened in September 1792, Égalité supported the radical democratic policies of the Montagnards against their more moderate Girondin opponents. Nevertheless, during the trial of Louis XVI by the Convention, the Girondins attempted to confuse the issues by accusing the Montagnards of conspiring to put Égalité on the throne. Égalité voted for the execution of his cousin Louis, but he fell under suspicion when his son Louis-Philippe, duc de Chartres (the future ‘King of the French’), defected to the Austrians with the French commander Charles-François du Périer Dumouriez on 5th April 1793. Accused of being an accomplice of Dumouriez, Égalité was arrested on 6th April and was, like his king cousin, sent to the guillotine in November. Supposedly, his last, impatient words to the executioner were: “Get on with it!”.

Such was his position as a prominent Bourbon, it was necessary that a portrait be commissioned to bolster a strong image of the duke of Chartres, as he was then known, within the court’s royal residences. Louis Tocqué (1696 – 1772), a dedicated follower of Hyacinthe Rigaud and Jean-Marc Nattier (his father-in-law), was a leading portrait painter whose first major commission was to paint the French Dauphin, Louis de France (1729 – 1765), in 1739 [Fig. 1]. His suitably regal depiction of a future king of France was so well-received that he was then commissioned to paint the Dauphin’s mother, Queen Marie Leszczyńska, the following year. Thereafter, whilst regularly exhibiting at the Paris Salon, he was effectively the portrait painter of choice for the royal family and their inner circle, including their Orléans cousins.

The prime portrait of the duke of Chartres, exhibited by Tocqué at the Paris Salon in 1755 as ‘Le Portrait en pied de Monseigneur le duc de Chartres, jettant du pain à des Cygnes, dans un Bassin’ may be considered one of the artist’s most accomplished and successful portraits. Now held in the Rothschild collection, this portrait was so successfully conceived that it was replicated twice; once by the artist – formerly in the collection of Sir Richard Wallace (1818 – 1890) - and again, here, by the Duke of Orléans’s court painter Pierre Delorme (c.1716 – 1776).[4] It was not unusual to employ a particularly skilled painter to produce variants of paintings in the family collections; such copies might, as in this case, be made of recent works or even of much older works of art belonging to the family. With so many residences, it was no surprise that particularly beloved paintings should be replicated, to be equally enjoyed in different locations and to celebrate the progeny of such illustrious families. The circumstances of our portrait’s commission are not known, but it seems likely that because Tocqué had moved to Russia in May 1756 to work for Empress Elizaveta, and because he had endured difficulty in being paid by his French patrons, he was unable to produce a third version of the portrait for the duke of Orléans.[5] Seemingly, and quite naturally, the duke turned to his official painter, Delorme, to fulfil this commission in Tocqué’s place.[6]

The quality of our portrait is such that it could convincingly appear to be an autograph, third version of Tocqué’s 1755 original portrait. However, the stamped inscription on the verso of the canvas, which likely dates to the early 1800s, clearly states ‘Par Delorme’ (i.e. ‘by Delorme’). Until recent research, the only regularly documented artist of that name was the neo-classical painter Pierre-Claude-François Delorme (1783 – 1859); considering the painterly technique is clearly consistent with works dating to the mid-eighteenth century, this Delorme was not the artist of this portrait.[7] Thanks to recently digitised archives, it has been discovered that an artist by the name of Pierre Delorme (c.1716 – 1776) was employed as the Duke of Orléans’s official court painter.

One of the earliest references to Pierre Delorme is within a dictionary of artists, printed in his lifetime, whose prints were in the Dresden print collection: “P. Delorme: Peintre du Duc d’Orleans, vivant a Paris, duquel nous avons…Le Portrait de Louis Philippe, Duc d’Orleans, par Lebeau.”[8] This engraving was published in 1775, when the duke was middle-aged and demonstrating why he was nicknamed ‘Le Gros’ [Fig. 4]. An earlier print from 1740, apparently derived from another original portrait by the artist, implies that Delorme must have been employed by Louis Philippe I for most of his adult life [Fig. 3]. There are no surviving records that detail his training or how he came to be employed by the Orléans household, however his name appears in two documents relating to the passing of his father, Claude Delorme, in 1759. Rather curiously, it states that his father and two brothers all served as postmasters in various areas of northern France - namely Paris, Normandy, and Lille - whereas Pierre, seemingly the nonconformist of the family, but notably the only beneficiary of rent from land owned by his father, is listed as “painter to His Serene Highness Monsignor the Duke of Orléans.”[9]

In a remarkable case of coincidence, a portrait depicting Henri IV of France by Frans Pourbus the Younger (presently with The Weiss Gallery), was copied by Pierre Delorme in 1763. The renowned dramatist Charles Collé (1709 – 1783) had been employed by the Duke of Orléans to assist him in writing roles for him in comedic dramas, of which he was a passionate, successful amateur actor. In Collé’s memoirs, he states the following within the entry for 3rd May 1763:

“On Tuesday 3 May, Mr. Delorme, painter-copyist of M. le duc d'Orléans, brought me separately a copy of the painting of Henri IV, which this prince gave me as a present. It was a gallantry he made to me on the occasion of my comedy of ‘Henri IV et le Meûnier’. This copy is taken from the original painting of this great king, which was painted two or three months before this hero monarch was assassinated. The next day I thanked M. le Duc d'Orléans, who said that this copy was so well done, that by placing it next to the painting, we could not distinguish the original.”[10]

Delorme’s somewhat unfair historical qualification as a career copyist could stem from how he was described in Collé’s memoirs; this description was directly referenced by Paul Mantz in his authoritative dictionary of portraitists active in France during the 18th century (1854) and, thus, his literal interpretation of Delorme being described as a ‘painter-copyist’ likely affected the artist’s subsequent reputation. Original portraits by Delorme, which challenge the convention that he was solely a copyist are recorded in various sources; the most important of which depict the duke of Orléans’s immediate circle, including our sitter’s sister, Louise-Marie-Therese-Bathilde of Orléans, and François Petit, the family’s doctor.[11]

The verso of our painting’s canvas has been inscribed with a description of the sitter, the name of the artist, and an inventory number identifying it as being from the collection in the château of Eu, part of the Penthièvre inheritance that was confiscated during the revolution. The château was returned to the family in 1814 (although Égalité’s widow, the dowager duchess of Orléans, only visited for a few days, in late September 1818), and following his mother’s death was then completely restored by the future king, Louis-Philippe, duke of Orléans, between 1821 and 1824. Following his assumption of the throne in 1830, Louis-Philippe continued to use the château until his exile in 1848 and in the 1870s, his grandson, the count of Paris, had a series of changes made by the master of neo-gothic, Eugène Viollet-le-Duc (1814 – 1879). The count of Paris’s son, the duke of Orléans, sold it in 1894 to his cousin, Prince Gaston of Orléans, husband of the princess imperial of Brazil, who had been given the title of count of Eu by his grandfather; it then became the property of the Orléans-Bragança family, the Imperial House of Brazil. A terrible fire damaged much of the château in 1902 but it was substantially restored, and the family continued to own it until selling it in 1954 (they had already sold the estate, some 9,300 hectares, in 1913) and since 1964 it has belonged to the town of Eu. A small part of the estate was retained by the descendants of the late Princess Isabelle of Orléans-Bragança, countess of Paris.

[1] According to Arnauld Doria, author of Louis Tocqué’s monograph, a notice from 1755, discussing the original portrait exhibited by Tocqué at the Paris Salon that year, states that the pond represented in the portrait is “one of the ponds of Saint-Cloud”. See Doria, 1921, p. 130.

[2] Becoming grand master of the grand lodge of France, later transformed into the ‘grand orient’; denounced for this during the revolution, he claimed that he had never really participated or attended the meetings of the latter.

[3] By his long-term mistress, Étiennette Marie Périne Le Marquis, a former dancer, the old duke of Orléans had had two sons, who became priests, and 3 daughters, one of the latter married, the other two entered nunneries. She ultimately fell out of favour (although receiving a generous financial settlement) and was replaced by the widowed marquise de Montesson. Such a marriage would not confer the husband’s rank on the wife, nor the right of succession on any children born of the relationship.

[4] It is worth noting that our portrait is the only version to have documented unbroken royal provenance. Whilst it is very likely that the Rothschild version (at the very least) must have originally belonged to the Orléans family, there are – seemingly – no surviving records indicating its early provenance.

[5] A. Doria, “Tocqué et Les Commandes Royales” from Gazette des Beaux-Arts, Paris, 1st July 1928, p. 164.

[6] The only feature that distinguishes our portrait from the other two painted by Tocqué is the third swan, which is situated behind the two in the foreground, which was perhaps a deliberate motif by Delorme to signify it being a third version of the Tocqué original.

[7] Doria included our portrait in his 1921 monograph of Louis Tocqué’s oeuvre, describing it as a ‘copie par Delorme…who was a copyist from the first half of the 19th century.’ Doria, 1921, p. 130.

[8] C. H. von Heinecken, Dictionnaire des artistes, dont nous avons des estampes avec une notice detaillée de leurs ouvrages graves, Leipzig 1790, pp. 585 – 586.

[9] A.L. Granges de Surgères, Artistes français des XVIIe et XVIIIe siècles (1681 - 1787), Paris 1893, p. 59.

[10] C. Collé, Journal et mémoires de Charles Collé sur les hommes de lettres, les ouvrages dramatiques et les événements les plus mémorables du règne de Louis XV, 1748 – 1772, Paris 1868, vol. III, p. 303.

[11] The portrait of Louise-Marie, presented as princess of Condé, might well have been designed as a pendant to our portrait. They remained together in the Orléans collection until they were split in the 1931 Vendôme sale (her portrait being lot 63). It is interesting to note that our portrait achieved 15,000 francs, which was the same amount paid for Nicolas de Largillière’s full-length portrait of the Princesse de Conti (lot 74) and other works by the great French masters.